If you make the winter run to Tahoe on a regular basis, it might seem like you’ve had to go farther up the hill to find snow in recent years.

Some scientists say it’s not your imagination.

Researchers have been keeping their eyes on the “snow line,” the point of elevation where rain turns to snow (or vice versa) during winter storms in the northern Sierra. What they found is that warming temperatures have pushed that level uphill by 1,200-to-1,500 feet in recent years.

If that sounds like a lot, even the lead author of the study was surprised when the data came in.

“Definitely,” says Ben Hatchett at the Desert Research Institute in Reno. “That was a lot of rise in the snow line.” Hatchett says it means more rain and less snow in the mountains overall — and the trend appears to be accelerating. “If this trend continues,” he adds, “that does not bode very well for the northern California watershed.”

California depends on the Sierra snowpack to store about a third of the state’s water supply, holding onto it well into the spring months when it can gradually melt into downstream reservoirs.

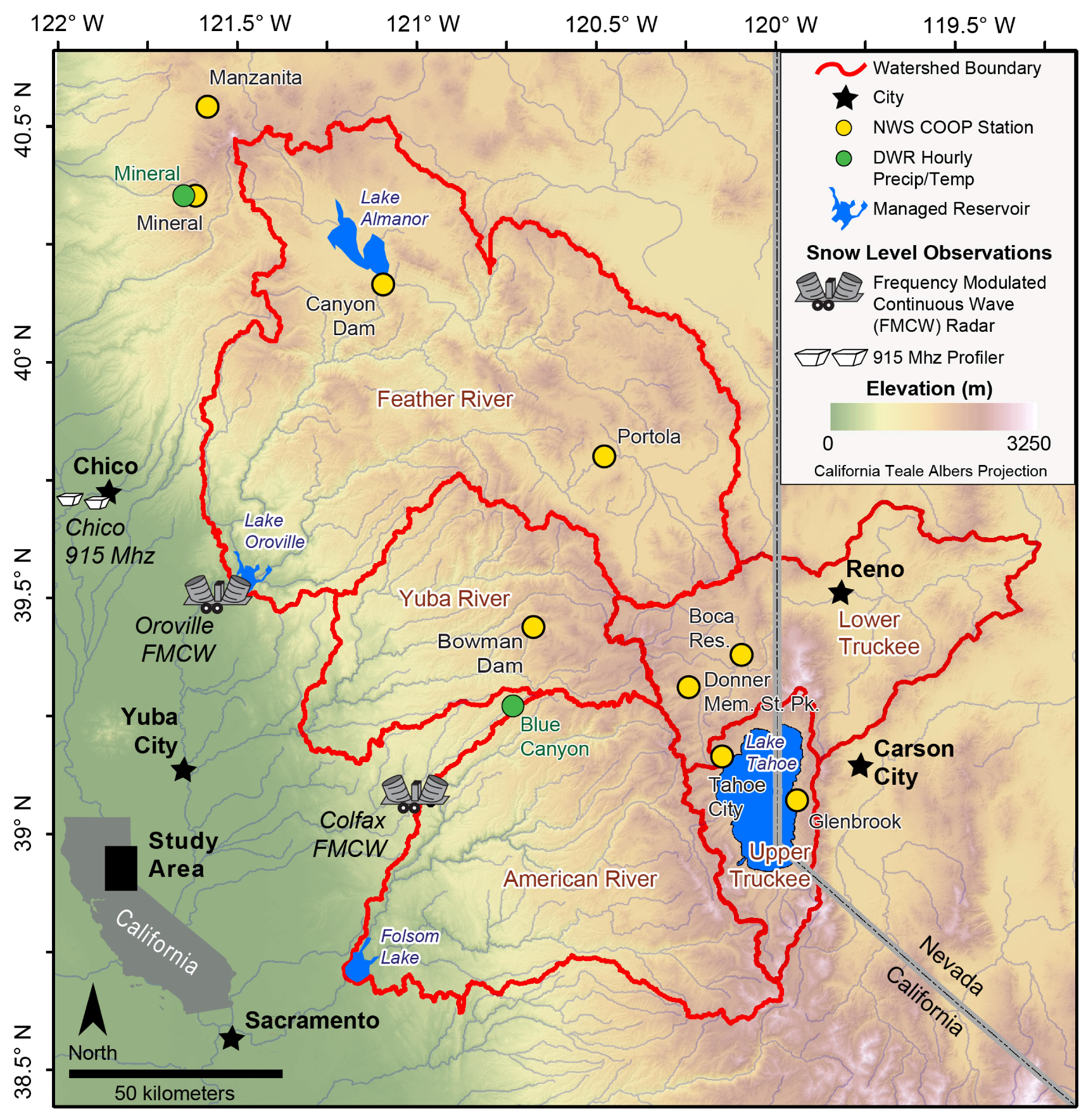

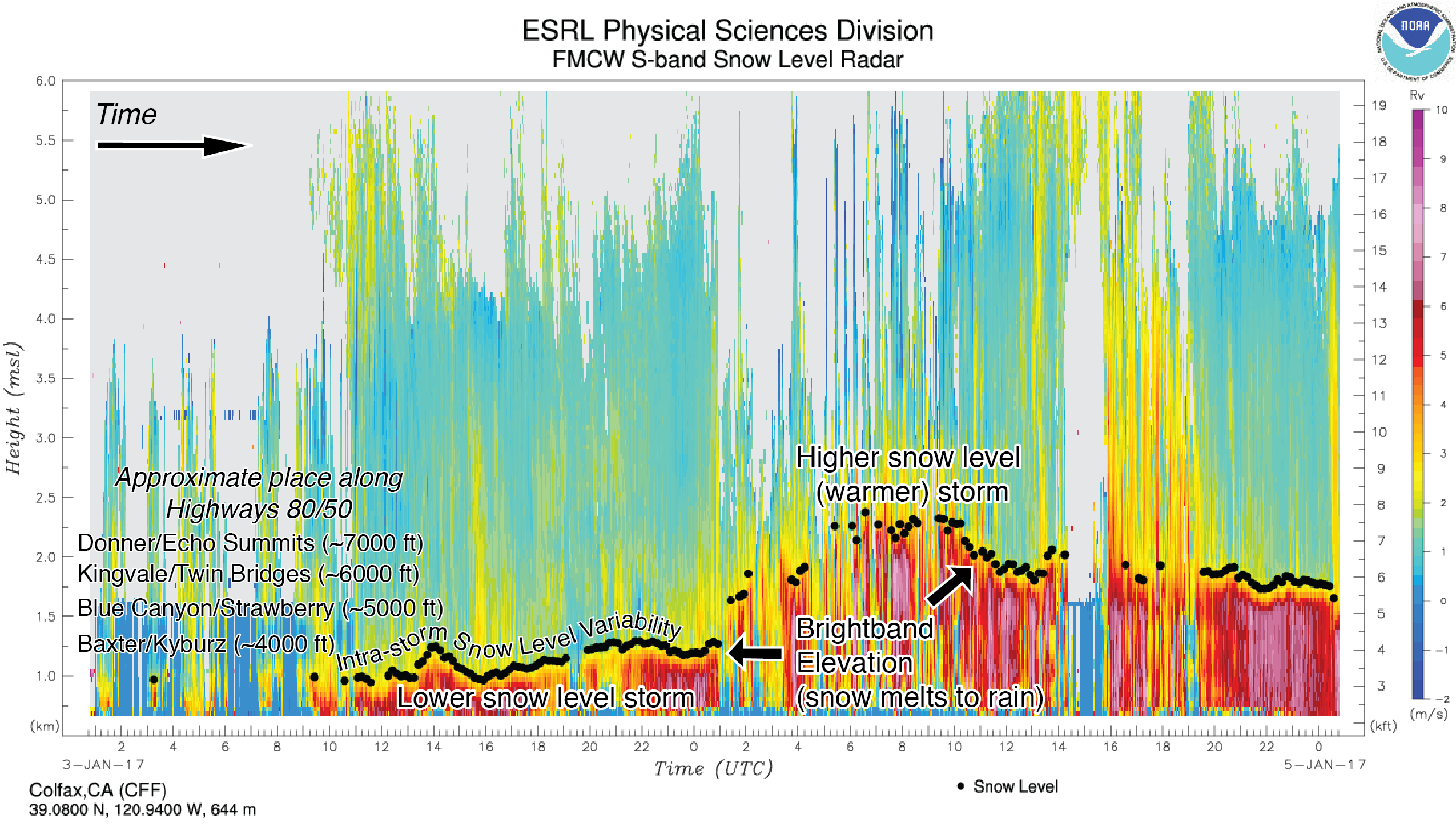

The study, published this week in the journal, Water, used specialized snow level-sensing radar to monitor the rain-snow transition line over a ten-year period. Then the research team cross-checked the results with temperature data to estimate changes in the snow line back to the mid-20th century. What they found, says Hatchett, was that the last decade saw the biggest decrease in the proportion of precipitation falling as snow compared to any decade going back to 1951 (the earliest point examined).

“It is striking,” says Roger Bales, who heads the Sierra Nevada Research Institute at UC Merced and was not on the study team. “This is a huge move uphill.” Though Bales advises caution reading too much into any analysis over a relatively short period of time, he adds that “the Sierra Nevada seems to be changing faster than predicted by the past ‘average’ climate projections.”

Some are more skeptical of the results. Noting the relatively short time span of the study, NASA snow hydrologist Tom Painter noted, “That’s not what one would call a trend.” Painter spends much of his time in the Sierra and above it with NASA’s Airborne Snow Observatory .

Hatchett acknowledges that the matter needs further study, but he does see an emergent trend and attributes much of it to warmer ocean temperatures and an increase in winter storms known as “ atmospheric rivers ,” which tend to be on the warm side and hence drop rain at relatively high elevations.

“What we’re saying is not that all storms are getting warmer,” notes Hatchett, “but in a statistical sense, we’re having more warm storms than we are cool storms. and that’s concerning because the future is projected to have more of these strong, warm storms.”

“Our results suggest that warmer ocean temperatures off the West Coast may be contributing to more precipitation as rain than snow in the northern Sierra,” adds Nina Oakley, regional climatologist at the Western Regional Climate Center and a member of the study team.

That alone would hardly come as a shock to most climate scientists, who for years have predicted this as a symptom of the warming climate. But the pace of the transition suggested by this study is arresting. The team found that three percent more precipitation fell as rain rather than snow in each year from 2008-2017 than in the previous five-year period.

“That could certainly change how we manage our water resources,” says Hatchett, “but if it’s a trend that continues, that’s certainly cause for much concern.”

That concern would extend beyond the water supply to Sierra ski resorts and the entire mountain ecosystem, which had developed around the presence of snow.

The study was a collaboration of researchers at the WRCC and its parent Desert Research Institute, several U.S. universities and the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration’s Earth System Research Laboratory in Boulder, Colorado.